Classical physics tells us that a distance of one meter in space is always one meter. In quantum physics one meter is also one meter, but the elimination of distance, or the approximation or acceptance of something, changes that object or at least contains a wider spectrum of interpretative possibilities, so that the comparative of focused concretization is a well facetted ambiguity in the sense of quantum physics.

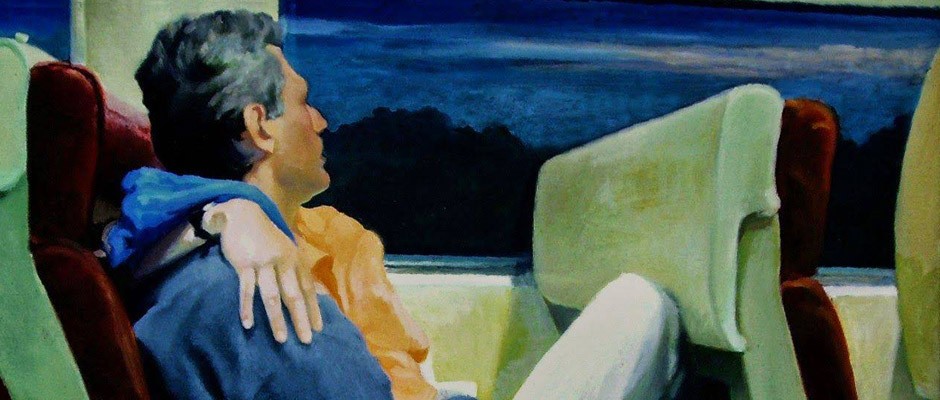

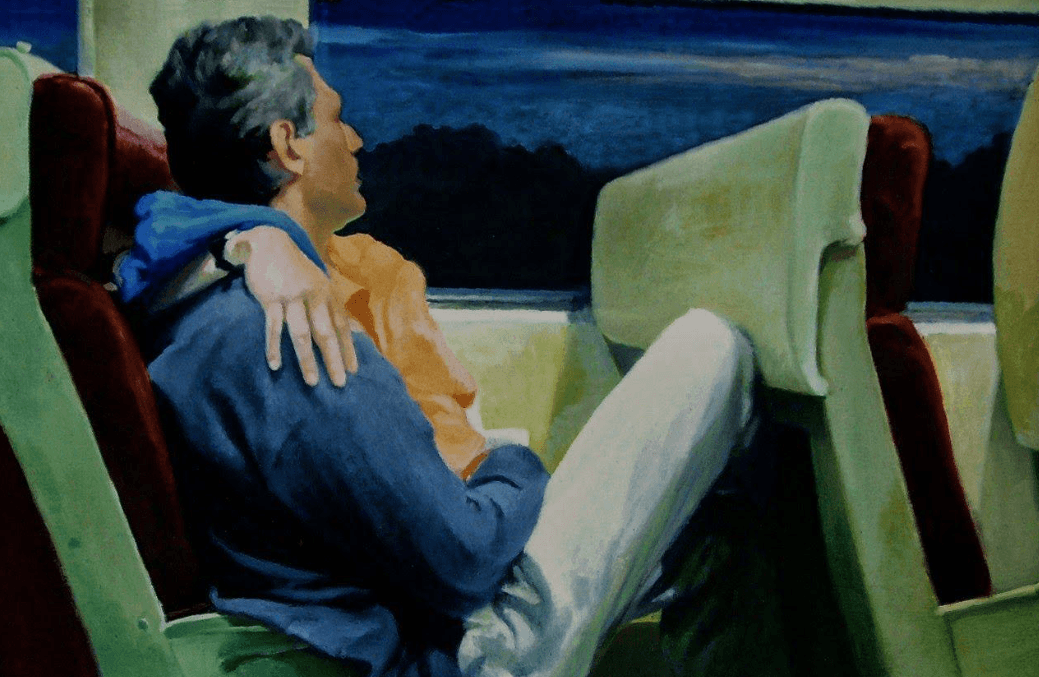

Nigel Van Wieck’s works function in a similar manner. On first glance we seem to see just what we see. The realistic pictures reveal for us a view of people on a beach, or at work, or involved in recreational activities, or in their domestic surroundings, or in public places. However, as we approach them they lose their unequivocal nature and one begins to ask oneself what is it that we see, or much more if this is everything we see?

Van Wieck has been living and working in New York, USA, since 1979. The fact that the artist is actually English is not apparent, in the least not in his works. They recall too much the works of American Realist artists, with whom he came in contact with after moving to America. At first it was the American Realist paintings of the late 19th century that impressed Van Wieck, such as those of Thomas Eakins or Winslow Homer. But even stronger was his fascination with the work of Edward Hopper, whose art he thought was exemplary and in whom he perceived a kindred spirit. The comparison between the oeuvre of Hopper and Van Wieck has understandably often been drawn. In fact there are numerous parallels between Hopper’s often isolated and introverted figures who are caught in an urban tristesse and the equally singular figures in Van Wieck’s work. Moreover, the artists are united in their frequent depiction of empty places, in their clear compositional structure and in a fascination with sharp light and shadow effects. But Van Wieck’s pictures seem more optimistic, his protagonists are, in spite of their isolation, less melancholy than Hopper’s protagonists. Although figures such as the young woman who looks dreamily out to sea in Van Wieck’s Here Comes Tomorrow are characterized by a strange melancholy, her momentary loneliness is voluntary and not ordained by society, nor indeed caused by herself. Characteristically, the figures in his works do not seem to be so inextricably caught up in their situation as in Hopper’s, but are merely caught at a specific moment in time. Thus, the central objective of his art is not to dissect American society, but to create subtle snapshots of the “American way of Life”, whose sense of distance and lack of movement make them seem all the more penetrating. What is exciting about the pictures is the indefiniteness of the narrative context, the puzzle as to what came before and after each painted moment. This lack of articulation in the holding up of time gives the works a cinematographic quality and makes their nearness to cinema more than clear. In this respect Sunday Evening is one of the most exciting pictures, as it draws our attention above all because of its viewer’s perspective: the steep viewing angle through a tripartite window into a couple’s apartment could almost be a “film still” from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.[1]

Read the whole essay by Sylvia Mraz.