Or To His Illusions About Islam?

Before the Rev. Jacques Hamel’s blood dried on the floor of his church, calls went out to place him on the fast track to sainthood. Hashtag beatification spread through Twitter: #santosubito, or “make him a saint now.” In this rush to canonize the murdered French priest, something crucial went missing.

There was a time the Catholic Church used the word dialogue differently than it does now. Historically, dialogue meant an opportunity to convey and defend the truths of the faith. It was never a companionable device to underplay irreconcilable differences and just get along. As employed today, dialogue with Islam is accommodating and uncritical, a faux-Franciscan burlesque of the real thing.

By contrast, in these feminized—gelded—times dialogue has dwindled into manners. Lady-like, the churches put down doilies, set out tea, and offer crumpets and compliments to those who would as readily accept our heads on a tray. They bide their time. We squander ours on unreciprocated courtesies. Meanwhile, their numbers grow.

A Martyr Offers His Blood

The difference came to mind reading commentary by the eminent Catholic historian Roberto de Mattei. Writing in Il Tempo, he called Hamel “the first martyr [in Europe] at the hands of Islam.” His essay on the slaying, translated forRorate Caeli, closed this way:

If Pope Francis announced the start of the process for Father Hamel’s beatification, he would give the world a peaceful but strong and eloquent sign of the will of the Church to defend its identity. If, on the other hand, he continues to be under the illusion about a possible ecumenical agreement with Islam, he will repeat the same errors of those wretched politics which sacrificed the victims of the Communist persecution on the altars of Ostpolitik. However, the altar of politics is different from the holy altar in which the unbloody Sacrifice of Christ is celebrated. Father Jacques Hamel received the grace of uniting himself to this sacrifice, offering his own blood, on July 26th.

But Hamel did not offer his own blood. It was sliced out of him. He was taken unawares, a victim, not a willing agent. He did not choose death in defense of his faith. He was caught by surprise and slaughtered on the spot.

A declaration of sanctity should rest on agency, not accident. We Catholics are quick to spill theological language promiscuously onto events that call for something sturdier, more stringent. Tutored from the pulpit by a generation of capons, we let language—the poetry of faith—become a siren song deflecting attention from implacable realities.

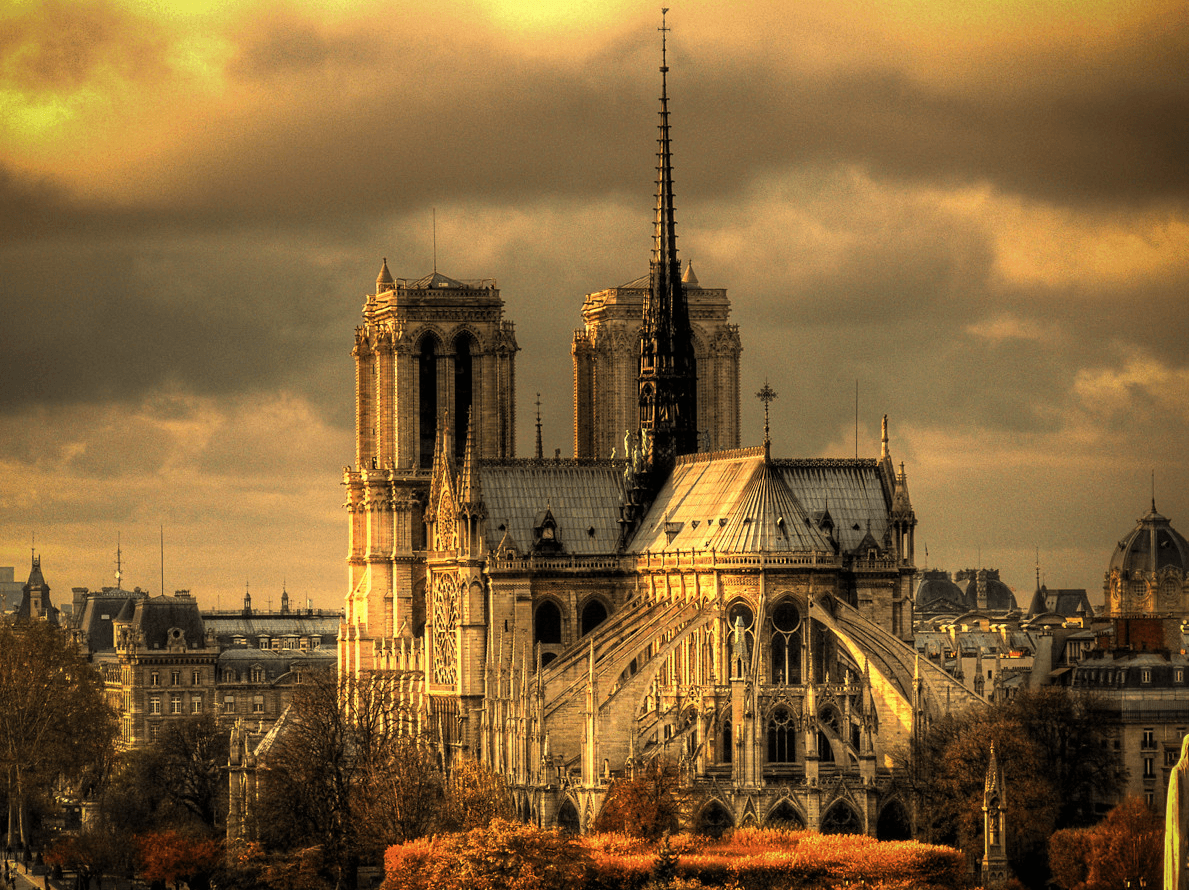

The historical Francis— Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone—would spin in his grave at the words of Sister Helene, one of the nuns taken hostage during the priest’s murder. Her captor turned from his kill to ask if she was familiar with the Qur’an. She answered, “Yes, I respect it like I respect the Bible.” Her words suggest equality between the two.

From Krakow where he was attending World Youth Day, Hamel’s superior, Dominique Lebrun, Archbishop of Rouen, intoned an equation of his own: “I have learned about the killings this morning in the Church of Saint-Etienne du Rouvray. There were three victims: the priest (84 yrs old) Fr Jacques Hamel and the two authors of the assassination.”

Compare St. Francis’ startling bluntness to an armed enemy: “It is just that Christians invade the land you inhabit, for you blaspheme the name of Christ and alienate everyone you can from His worship.” Biographer Frank Riga finds no indication the saint ever instructed his friars who went on mission into the Muslim camp to learn the Quran or honor the tenets of Islam. Il Poverello, as he was called, was not a man with patience for multicultural niceties.

Love Doesn’t Mean Acquiescence

Set aside, if you can, all horror at Hamel’s murder. Look past, please, all warranted sympathy for this good man and his terrible end. There remains a question: Was the priest a martyr for the faith or to his own illusions about Islam?

By all accounts a kindly man, Hamel served in a parish committed to the very illusion of ecumenical agreement with Islam that de Mattei abhors. The Belfast Telegraph reports the nuns gave reading lessons to Muslim kids in the tower blocks. Church authorities soared above such neighborliness. Courting dhimmitude, they donated the land beside Hamel’s church to local Muslims to build the mosque his two young killers attended. During Ramadan, the parish hall “and other facilities” were given over to Muslims. (In terms of Islamic jurisprudence, the mosque and the ground under it belong forever to the eternal ummah. The archdiocese has ceded a portion of Normandy to the caliphate. Allah be praised.)

In his last pastoral letter, Hamel called for communities to live together and “accept each other as they are.” But accepting Islam means recognizing its totalizing nature. Authentic acceptance is unsentimental. It is a prod to staying watchful. To befriend Muslims as individuals does not cancel the necessity to know Islam’s history, its millenarian ambitions, and its enduring theological imperative toward violence.

Christian charity does not entail any obligation to accommodate Islam’s muscular expansion in the West. One way to love the enemy is to defeat him. Yet Hamel’s parish was actively lending itself to Islam’s ascendancy. Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray is a lesson in the price Christianity pays for the fanaticism of profligate mercy.

Maureen Mullarkey

London’s Independent reports that “dozens of Muslims in France and Italy attended Catholic Masses as a gesture of interfaith solidarity following the attack on the priest.” Only dozens? Out of how many million?